Be sure to pick up the September issue of America’s longest running blues publication, LIVING BLUES!

Remembering Bob Koester

1932–2021

By Jim O’Neal and others

Bob Koester, owner of Delmark Records and the Jazz Record Mart in Chicago, was for more than 60 years a mentor and friend to many in the blues world, and he leaves a lasting legacy as one of the genre’s most important figures. We take a look back at his career and influence on the music we love.

http://digital.livingblues.com/publication/?i=718906&article_id=4100630&view=articleBrowser&ver=html5

LIVING BLUES #274 EXTRAS: REMEMBERING BOB KOESTER

Included in this Extra Edition are images and remembrances that we didn’t have room for in LB #274.

It was Delmark’s first LP by Big Joe Williams that caught my attention. I was by chance able to record my second Arhoolie release, LP 1002, by this incredible blues singer in the fall of 1960 in my cabin in Los Gatos, California! I probably first met Bob in person in 1964 when I was hired to accompany Lightnin’ Hopkins on the American Folk Blues Festival tour of Europe while Bob was on that tour with Sleepy John Estes and Hammie Nixon. After that, Bob was always a most gracious host when I visited Chicago, and took and guided me to the best blues clubs. His love for blues and all types of jazz was remarkable and his store was able to do well since his audience was solely focused on those two genres which had gained a large worldwide audience. A great human being and devoted record man! RIP!

—Chris Strachwitz (Arhoolie Records and Down Home Music)

I first “met” Bob (via US Mail—I regret never meeting him in person but we got to know each other well via mail and phone calls over a 50-year time span) in 1962 when I, as a 14-year-old piano blues enthusiast in the making, bought a copy of The Dirty Dozens by Speckled Red (Rufus Perryman) from [then] Delmar Records. I was familiar with Speckled Red’s 1930s recordings and I had gotten to know his younger brother Piano Red (Willie Perryman) during breaks at dances he performed for in Birmingham, Alabama.

I began selling traditional blues and jazz records by mail through my fledgling magazine, Music Memories, and for about a six-year period I bought a lot of LPs from Bob and he, in turn, bought many copies of the first blues LP I issued, Barrelhouse Blues and Jook Piano by the late Robert McCoy on my (then) Vulcan label.

Business—and the friendship—increased when my magazine merged with the Jazz Report magazine Bob had started earlier. I recall Bob being very pleasant to work with and maybe that’s because I was just a kid. Once, in lieu of a small debt I owed to Delmark (for some reason he and I both added a “k” to our record label names—mine, because of a trademark issue, had become “Vulkan” instead of “Vulcan”), I sent him (with Bob’s okay, of course) a field tape I’d made of a great Birmingham bottleneck guitarist and singer named Charley Barker.

Forty years later, when Bob reissued my original LP by Robert McCoy, I asked him whatever happened to the really good tape by Charley Barker. Bob laughed, saying he vaguely remembered it and promised me, “It’s still gotta be in the building somewhere!”

And thinking back on that reissue, I remember Bob and me going back and forth several times by phone and by mail on the subject of the liner notes he asked me to write. If I recall correctly, Bob had a very specific word limit in mind—maybe 1,500 words?—and I just wasn’t able to get the number down to lower than, say, 1,700 words. Bob insisted I keep editing but I finally asked him if he could possibly live with my 1,700 words if I gave up the usual liner note fee ($100?). He readily agreed. I still read those liner notes maybe once a year and am still very proud of them (although one reviewer said they were “akin to a suicide note!”). Thanks, Bob, for publishing them as written. :-}

Meanwhile, a blues enthusiast friend in Belgium or Germany (and I’ve forgotten his name) bought the rights to and the original studio tapes of Robert McCoy’s second album on my label with the promise that he would see those reissued at some point, probably through Delmark. A year or so later, I called Bob to ask him about it and he told me that it was too soon to issue another CD by Robert but that he had talked to my friend (who may have even sent Bob the tapes) and told him that those tapes would have to be on the “back burner” for now. So now I wonder if they, too, aren’t “in the building somewhere.”

I hope so. And I hope Bob’s spirit is also “in the building somewhere”—watching over Delmark and watching over the Charley Barker and Robert McCoy tapes and hoping—along with me—that they’ll soon make their way to the “front burner.”

—Patrick Cather

I first met Bob when my brother John was working for JRM. He was a mentor to so many. I remember all of the knowledgeable people that worked at the store as apprentices. And Bob ruled that roost with his crew . . . strict, but willing to impart his vast wisdom. Whether it was his immense knowledge of the film world or befriending Big Joe Williams, he showed his multiple personalities . . . from his sometimes-rough exterior to a behind-the-scenes heart of goodwill. And, when he released our Magic Sam Live at Ann Arbor, he agreed to pay Sam’s widow all of the advance money we declined. And Bob never forgot his allegiance to St. Louis and Chicago jazz, particularly the early years of the avant-garde.

—Jim Fishel

Bob and Sue Koester created sweet home Chicago for Steve Tomashefsky and me.

Because we loved the blues, we moved to Chicago in December 1972. We knew hardly anyone; had no jobs, nor a place to live. We had absolutely no idea what was in store for us. But, then, Steve got lucky; Bob hired him. Then, just a couple weeks later, at the end of that January, we both got lucky: we were celebrating my birthday at Theresa’s with Bob and Sue (and Junior Wells). Talk about a sweet home!

For the next decade, almost every Saturday night, we were part of the “Blues Amalgamated,” a group of blues-loving friends at whose center were Bob and Sue. Thanks to Bob’s Chicago-home-making, Steve and I heard pretty much all of the Chicago-Mississippi blues greats of that era. (As Steve summed it up in the liner notes to Junior Wells—Live at Theresa’s,an album he and Bob produced together: “Man, you should’ve been there.”)

Here’s that list: Junior Wells, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Big Joe Williams, James Cotton, Pinetop Perkins, Little Milton, Tyrone Davis, Denise LaSalle, Otis Clay, Syl and Jimmy Johnson, Bobby Rush, Pops, Mavis, and the Staple Singers, Jimmy Dawkins, Sunnyland Slim, Fenton Robinson, Jimmy Reed, Hound Dog Taylor and the Houserockers, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Willie Dixon, Carey Bell, Hubert Sumlin, Eddie Shaw, Honeyboy Edwards, Blind John Davis, John Littlejohn, the Aces, Eddie Taylor, Magic Slim and the Teardrops, Johnny Christian, Matt Murphy, Cicero Blake, Big Walter Horton, Lefty Dizz, Johnny Dollar, Byther Smith, Big Moose Walker, Artie “Blues Boy” White, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Roosevelt Sykes, and Little Brother Montgomery.

These musicians, along with dozens of others less well-known, were just out our proverbial doorstep—because Bob created the path down that step and across town for us, the rest of the Blues Amalgamated, and millions of other blues lovers around the world. Lest you ever doubted Bob’s gift to the world; never doubt.

While Steve and I have been fortunate to make many dear friends over the decades of our life together, Bob and Sue are in a group unto themselves. They completely unselfishly rooted us in an experience of theirs we too wanted, an experience that remains 50 years later among the most formative of our entire lives. Today, a half century after our move to Chicago, over a half century since hearing my first Delmark artist on record—and live (the latter would be Luther Allison in 1970), I continue to treasure Bob’s gift to the world: to constantly remind us that people from vastly different backgrounds can come together in a common artistic experience that both creates shared joy and leads to greater understanding and respect for one another.

Thank you, Bob.

—Rebecca Sive

In recent years, one of my favorite activities was to visit my friend and music mentor Bob Koester during his Saturday afternoon shift at his Jazz Record Mart. Over the years, he introduced me to the recordings of many blues, R&B, and jazz artists. I find it interesting that Bob was perhaps more fascinated with record labels and their histories than he was with the artists themselves. In addition to music, another thing that Bob and I shared in common is that we both had polio—and both walk with a limp. If you were to hold a walking race between the two of us, there would be no winner—simply two losers . . .

One weekend, we went for lunch in the immediate neighborhood and on the way back from lunch a rather weird thing happened. As we ambled around the corner of State and Illinois, we passed a middle-aged Black man, who seemed to be living on the streets. He was sitting on the sidewalk surrounded by a platoon of plastic bags and a boombox. As we passed, the guy shouted out, “Bob Koester!” And he stood up and gave Bob this big hug! In the midst of this unexpected embrace from a total stranger, Bob, who was sort of sheepishly bemused and at a loss for words, introduced me to his new friend. “Hey, whoever you are, I want you to meet Steve Cushing.” And before Bob could finish the introduction, our new friend yelled out, “Blues Before Sunrise!” and came over to shake my hand. “Man, I’ve been listening for years!” What made it even more surreal was that as all this took place we were surrounded by a crowd of young Black people, high school–aged kids, waiting at a bus stop. They were all sort of amused and fascinated. It turns out that the two fat, beat-to-shit, limping white guys are minor celebs—and the only guy who recognizes them is a middle-aged Black man living on the street. I think half the kids were looking around for the camera—sure that the whole situation was a prank.

—Steve Cushing

[Ed. Note: Steve Cushing, longtime radio host of Blues Before Sunrise, interviewed Bob Koester during Delmark’s 50th anniversary on May 25, 2003. He rebroadcast this interview in 2021 just weeks before Koester’s death. See http://www.bluesbeforesunrise.com.]

I will forever cherish my time at Delmark Records, especially my working relationship with Bob Koester. I feel so honored and privileged to have worked closely along side one of my “behind the scenes” musical heroes, who was such an important and influential contributor to the world of blues and jazz. I really wish I had documented some of our conversations because Bob had such an encyclopedic mind with fascinating and often hilarious music stories to share. I loved our conversations because they were so interesting and informative, although they would careen off subject quite often; I think his blues name should have been fondly “Good Ramblin’ Bob!”

There are so many special points to share about Bob, with one of my favorites being that he singlehandedly brought countless blues fans to Chicago’s West and South sides for their first time experiencing live blues in funky, gritty neighborhood clubs. I’ve been told that back in the ‘60’s (before live music gig listings in the paper and obviously computers) Bob had a paper posted at his Jazz Record Mart listing when and where the blues shows were taking place and he would take a caravan of blues fans every Saturday night to seek out the best live Chicago blues. Bob lived a truly remarkably fascinating and musically rich long life with his loving wife (and super star in her own right) by his side. Thank you, Bob and Sue Koester for your encouragement, support, and all of the fun times!

Kevin Johnson, Proud Papa Promotions & Publicity

https://www.npr.org/2021/05/15/997105714/remembering-delmark-records-founder-bob-koester

https://www.americanbluesscene.com/remembering-chicago-icon-bob-koester/

Remembering Chicago Icon Bob Koester

Cary Baker / Conqueroo

“Bob could usually be found behind the counter. And he took hours over the years to answer my ceaseless barrage of questions — about blues artists, blues bars (which I was too young to enter legally), record labels, record distribution, record collecting.” – Cary Baker

I learned just now that one of my mentors in life, work and musical appreciation has died. Bob Koester, founder of Chicago’s Delmark Records label and Jazz Record Mart store has passed. He was 88 years old.

Delmark, of course, was the label that brought us at least five of my Top Ten Desert Isle Blues Discs of all time — albums by Magic Sam, Junior Wells J.B. Hutto & the Hawks, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Sleepy John Estes, Jimmy Johnson, Carey Bell, and Jimmy Dawkins. And then there was jazz: The Art Ensemble of Chicago, Anthony Braxton, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Muhal Richard Abrams.

I even suggested the title for Magic Sam’s second album: Black Magic. Bob informed me that Living Blues co-founder Jim O’Neal had already chimed in with that title idea as well. And so it became the title.

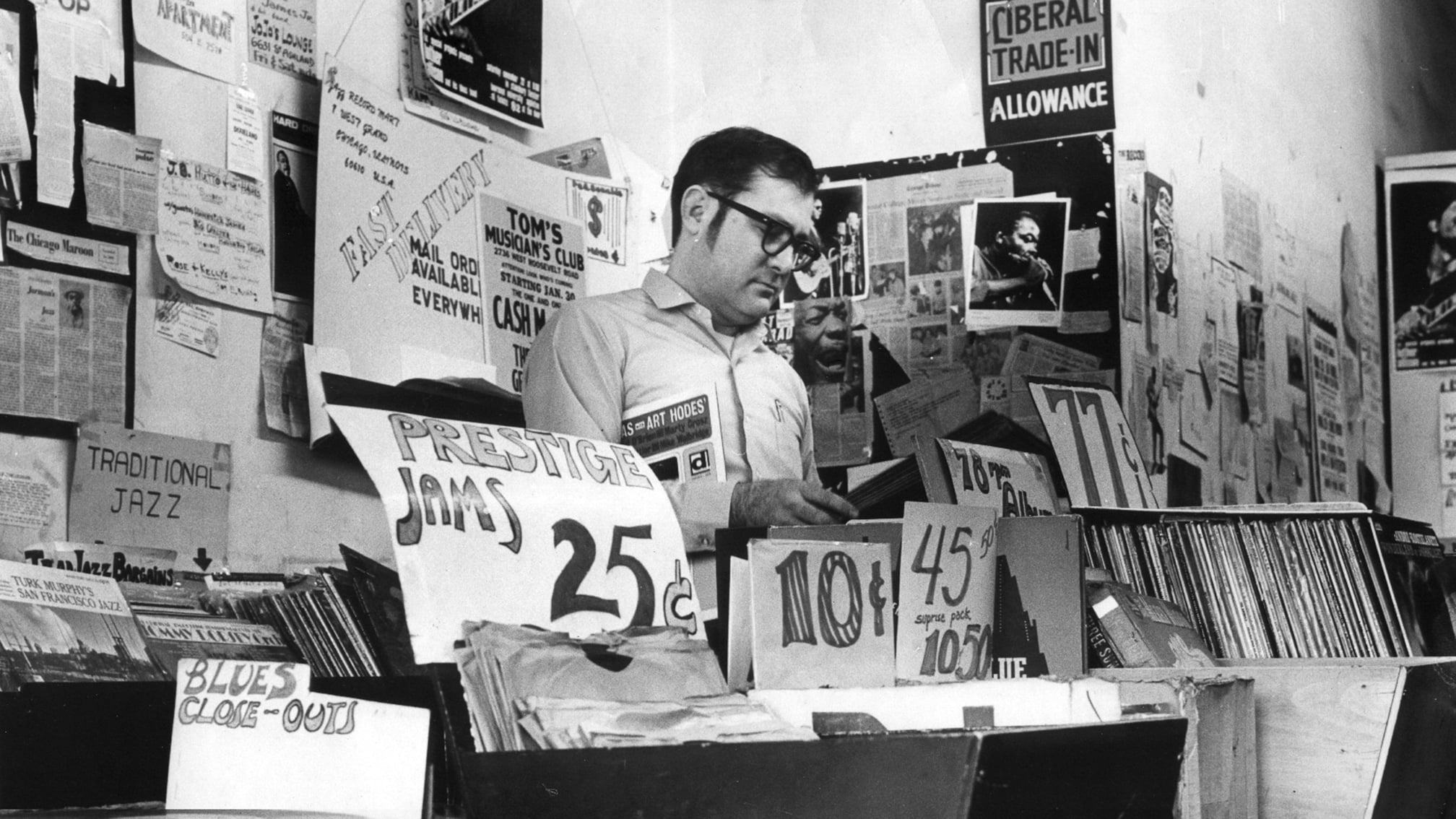

When I was a 13-year-old kid in the Chicago suburbs, I became aware of blues, and suddenly needed to know everything there was to know. So at 14, I got on the El train from my hometown of Wilmette bound for the corner of W. Grand Ave. & N. State St., which was the original Jazz Record Mart location. Bob could usually be found behind the counter. And he took hours over the years to answer my ceaseless barrage of questions — about blues artists, blues bars (which I was too young to enter legally), record labels, record distribution, record collecting. I was 14 and he was (by my math) 47. But we had a sort-of friendship. He encouraged me to publish my blues fanzine, Blue Flame.

He was a very different kind of adult from my classical music parents. And of course I always bought lots of records: LPs, 45s and 78s. There was a 25 cent Prestige jazz 78 RPM bin which one day became a 39 cent Prestige 78 bin. Inflation was a bitch!

Over the years, I went to the Jazz Record Mart about one Saturday per month. While there, I met Moondog (in full Viking regalia), Big Joe Williams, Sunnyland Slim, Jimmy Dawkins, Wild Child Butler and future Alligator Records founder Bruce Iglauer. In conversations with all of them, you could say I learned a bit about life.

I had lost contact with Bob around the time I left Chicago for college in rural Illinois, and certainly by the time I left for California. The last time I saw him was at a Blues Foundation function at B.B. King’s Blues Club in Universal City, Calif. A few years ago, he wisely sold Delmark to two great younger music freaks, Julia A. Miller and Elbio Barilari, whom I like a lot, and who are finding some 21st Century solutions for keeping the Delmark tradition relevant and accessible (like the Jimmy Johnson livestreams every Saturday).

I will be forever grateful to Bob Koester, not only for his life’s work, but for not writing off this suburban teenager. It meant a lot. In fact, it meant everything.

https://www.americanbluesscene.com/remembering-chicago-icon-bob-koester/

Bob Koester: The Purest of Purists

Remembering the life of the man who kept the spirit of jazz and blues alive and thriving in Chicago James Porter 6 Comments

Every time I exit the Red Line subway at Grand Ave. in Chicago, I keep half-expecting my feet to take me to the Jazz Record Mart.

Even though it ceased operation in 2016, I was a habitual shopper for years. As a steady customer, music writer and diehard blues fan, I was in and out of the JRM/Delmark Records universe for years. Besides being friends with various musicians and employees, I penned the liner notes to a Dave Specter album, and Rockin’ Johnny Burgin recorded a song I wrote. The owner, Bob Koester, was famously known for talking at length about random blues and jazz minutiae to anybody within earshot.

I was on the receiving end more than once; one of the first times I went to the JRM as a teenager, without my father, he started rambling on to me, at length, about the covers Andy Warhol painted for Blue Note albums. He never remembered my name until maybe four years before they closed down (and then he forgot again). Just the same, I dug hearing the stories, whether they were told directly to me or overheard while I was looking through the 45s. Prior to his passing on May 12, aged 88, the man led a full life, and did a lot to raise the profile of jazz and blues in Chicago – and elsewhere.

My father used to shop here in the 70s, and as a grade-school kid I used to tag along with him. The place was still on Grand Ave. then, and seemed as esoteric as a record store could get, with handwritten signs (this was pre-computer age), a smallish space and just about every Etta James and Bo Diddley record ever issued. (And mostly male customers, although they did have a small spike of females when CDs were hot.) By the time I started going there on my own in the 80s, it was still on Grand but the space was bigger. As a teenage blues fan who didn’t know too many other blues fans (yet), I was gratified to be shopping in a Madonna-free zone. Some of the older wax hounds I knew may have found future collectors items for pennies on the dollar while I was barely in the first grade, but I still managed to dig up some classics in the 80s and beyond. I still kept buying records there through two more locations, as well as attending all kinds of live shows in the space, from Terry Callier to Louisiana Red. Koester wasn’t there every day, but he made his presence known when he did.

His irascibility was no joke; during the first few years of the Chicago Blues Festival, the Jazz Record Mart had a stand. In that environment, Koester just stopped short of cracking a whip as he loudly barked at his employees about some issue or other. Once, I was in the shop talking with a friend and recommending an excellent Delmark CD compilation called Chicago Ain’t Nothing But A Blues Band. This anthology compiled a gang of sides recorded for the Atomic-H label between 1958-60, with Eddy Clearwater and others. As I was telling my friend, a number of the best cuts sounded like Chuck Berry-styled rock & roll (including the two excepted below). When Koester overheard me refer to one of his albums as “rock & roll,” he looked straight at me and raised an eyebrow as if to say “are you sure?” Robert Gregg Koester, patron saint of blues and jazz, was the purest of purists.https://www.youtube.com/embed/ZFpJMeWStEc?feature=oembed

AUDIO: Johnnie Rodgers “I Am A Lucky, Lucky Man”

Much has been said about whether blues and jazz are dead, alive, in rehab, in the ER, or on the way back. Bob Koester, in the city of Chicago, did as much for both musics as anyone. For 57 years and four locations, from the tail end of the 78 era up through the advent of mp3s, the Jazz Record Mart managed to remain Chicago’s leading retailer of two of America’s most indigenous musics. There was serious competition through the years, like Rose Records and Tower Records, both now gone. Even though those shops had entire blues and jazz rooms (and the inventory to back it up), the Jazz Record Mart gave fans of this music their own shop.

And in the great tradition of record stores who have spinoff labels, the JRM gave us Delmark Records, which still continues to document, and reissue, classic blues, jazz and the occasional act that is neither (like singer-songwriter Frank Morey, as well as John Prine, who almost recorded for the label until Atlantic stole him away). Independent labels have always had the corner on jazz and especially blues, but Delmark more or less ushered in a new breed of label that existed not to create hits, but to document living traditions that continued to be steady sellers for years.

A couple of years after Delmark was founded in 1958, over on the West Coast, the Arhoolie label was founded by Chris Strachwitz. Folkways Records in NYC preceded both by maybe a decade, and in the next few decades, various blues indies came and went: Rounder, Flying Fish (no longer active), and probably the most visible of all, Bruce Iglauer’s Alligator label, which was founded in ’71 and did a lot to jumpstart the blues resurgence of the 80s and 90s. However, the Delmark label casts a shadow across most of these companies as a sort of godfather of the scene. Magic Sam’s West Side Soul and Junior Wells’ Hoodoo Man Blues continue to make Essential Blues Albums lists long after their release. This is without even mentioning the other outstanding blues acts that passed through Delmark’s portals over the years: J.B. Hutto, Sleepy John Estes, Luther Allison, Otis Rush, Jimmy Johnson, Dave Specter, Rockin’ Johnny Burgin, Toronzo Cannon, Lurrie Bell, Johnny B. Moore, Big Joe Williams, Jimmy Burns and many others.https://www.youtube.com/embed/3lPtSVN5QVY?feature=oembed

AUDIO: Eddy Clearwater “Hillbilly Blues”

In addition, Delmark has done more to expose the art of blues piano more than any other company (aside from Steven Dolins’ label, The Sirens). The piano has always been an underrated element of the blues, and the label always worked overtime to keep it in the public eye, even releasing a compilation called Blues Piano Orgy. The first Delmark blues album was by Speckled Red back in ’61, and they continued to document the likes of Roosevelt Sykes, Aaron Moore, Curtis Jones, Sunnyland Slim, Piano Red, and the extremely overlooked Big Doo Wopper, a blind street musician who released two lost classics on the label in the early 2000s. Over on the jazz side, Delmark distinguished itself by satisfying the traditionalists and the adventurous end. Big band, Dixieland, straight-ahead bop and the avant garde were all equally represented in the Delmark roster, which continues today through new owners Julia A. Miller and Elbio Barilari. The store itself closed down in 2016, victim of higher rents. Koester soon reappeared with a new store, Bob’s Blues & Jazz Mart, on Irving Park Road, which will remain in business, according to the Koester family.

Towards the end of 2020, Koester suffered from a stroke that he didn’t quite recover from. While he had already left Delmark in the hands of the new owners, he still continued to show up at the new store, until his passing. He still felt that urge to keep busy. Several Delmark recordings have become part of the blues/jazz legacy, from Magic Sam to Sun Ra, from Big Joe Williams to Kalaparusha. Thanks to Koester’s efforts, these seminal recordings will never fall out of the canon.

Bob Koester, who ran Chicago’s Jazz Record Mart, Delmark Records for decades, has died at 88

WXRT DJ Terri Hemmert called him ‘a force of nature,’ the mart ‘one of the coolest record stores in the world’ and said she’d buy a record just because it was on his label.By Maureen O’Donnell Updated May 12, 2021, 6:17pm CDT

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69276928/merlin_36987504.0.jpg)

Bob Koester, longtime owner of Chicago’s legendary Jazz Record Mart and founder of the Delmark Records label, died Wednesday at 88.

He had had a stroke and was in hospice care, according to his son, also named Bob.

The store he ran for decades at various downtown Chicago locations drew legions of jazz and blues fans from around the world.

Bruce Iglauer, founder of Chicago’s Alligator Records, called Mr. Koester “a hero not only to blues and jazz but to Chicago music.”

Mr. Koester was one of the first to capture the sounds of the city’s South Side and West Side blues clubs, according to Iglauer, who once worked for him. Iglauer said he gave artists free rein in the studio.

That approach resulted in classics including “Hoodoo Man Blues” by Junior Wells.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22510454/merlin_37926561.jpg)

Mr. Koester lifted some forgotten artists from the 1930s out of obscurity, getting them to record for the first time since they’d made it big in the era of 78 rpm records. He also was one of the first to record the country-flavored blues of Big Joe Williams and Speckled Red.

In an online tribute, longtime WXRT DJ Terri Hemmert called Mr. Koester “a force of nature,” the Jazz Record Mart “one of the coolest record stores in the world” and said she’d buy a record just because it was on his label.

“If it was on Delmark, I wanted to hear it,” Hemmert said.

Mr. Koester called the Jazz Record Mart the “World’s Largest Jazz and Blues Specialty Store.” He first opened the store on Wabash Avenue near Roosevelt University.

He met Sue, his wife of more than 50 years, at his next address, 7 W. Grand Ave. She was working nearby at the American Medical Association and came in to buy a record.

He moved the store to 11 W. Grand Ave., then 444 N. Wabash Ave. He was at 25-27 E. Illinois St. when he closed the business in 2016, citing high rent.

That year, he opened the smaller Bob’s Blues & Jazz Mart at 3419 W. Irving Park Rd., which hosted concerts and his 87th birthday celebration last year.

“He was pretty much always doing what he wanted to do,” his son said.

“The Jazz Record Mart was an institution, and Bob Koester was the institution behind the counter,” said Frank Alkyer, editor and publisher of DownBeat magazine. “He had one of the most successful record stores in the United States that focused on jazz and blues.”

Born in Wichita, Kansas, Mr. Koester sold records from his dorm room at St. Louis University before dropping out and, with a partner, starting the Blue Note record shop in that city in 1952. “We stole the Blue Note label logo for our sign,” he once told the Chicago Sun-Times.

He struck out for Chicago in 1958 after founding Delmark Records about five years earlier. The label recorded stars including Wells, Williams, Otis Rush and Magic Sam. It also reissued music by artists including Dinah Washington and produced the avant-garde jazz artists of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians.

“Bob Koester was the first person to issue any record by the AACM,” said jazz critic Howard Mandel, president of the Jazz Journalists Association.

Mandel said the AACM’s style wasn’t Mr. Koester’s favorite, but “he believed in what they were doing . . . Bob was not doing this thinking he was going to make money. He believed there was music happening in Chicago that he could really launch.”

Mr. Koester sold Delmark in 2018.

He knew plenty of jazz greats and a few rock legends. Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin and Bryan Ferry were among those who dropped in.

And he’d talk of how he was responsible for the name of Iggy Pop’s band, the Stooges, telling people that one night when the singer was staying with him he awoke to find Pop and his buddies playing loud music and bouncing off the furniture. As The New York Times later wrote, he threw them out, shouting, “You guys are a bunch of stooges.

He allowed that he could be irascible. He’d admonish customers to close the door so the heat wouldn’t escape.

A fan of classic movies, he’d invite friends over for screenings from his extensive film collection.

“I wanted to be a movie cameraman, but I got seduced by the music,” he once said.

Mr. Koester was a member of the Blues Hall of Fame but didn’t let that go to his head.

Asked about his legacy, he’d say, “I recognized good talent when I heard it,” according to his friend John Holden.

In addition to his wife and son, Mr. Koester is survived by his daughter Kate, brother Tom and two grandchildren.

Bob Koester leaves a colossal legacy in Chicago jazz and blues

For nearly 70 years, he owned the Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records—and though his businesses could be “crazy town,” they helped nurture thriving communities.by Howard MandelMay 19, 2021

Bob Koester, who died May 12 at age 88, knew what he liked—and what you should like too. For nearly 70 years, he owned Chicago’s Jazz Record Mart (and the Delmark label), and it was completely in character for him to snatch an album from the hands of an earnest young shopper.

In 1968, that shopper was me—I’d picked up a copy of Muhal Richard Abrams‘s debut LP, Levels and Degrees of Light, whose surreal cover painting and saturated colors promised something exotic and strange made right here. I was more than eager to hear it, but Koester—still black-haired, wearing glasses, not graceful, not yet 40—had other ideas. “You can’t understand that,” he insisted from behind the cash register, flapping the Abrams LP in my face, “if you haven’t heard this.” He thrust out The Legend of Sleepy John Estes, adorned with a photo of an old Black man with a guitar that looked like something from Picasso’s Blue Period.

He slid the Estes LP onto the turntable that was the throbbing heart of his warrenlike storefront, then located on Grand at State, upstairs from an el station and between a steam-table diner and a currency exchange. Out came the ancient voice of Sleepy John, groaning about mean rats in his kitchen, while he picked limply at his instrument with backing that sounded like a jug band—exactly the type of folksy stuff I wanted to ignore. I capitulated to Koester and bought it to get the Abrams album, and I listened dutifully to both. Eventually I caught on. The breadth of the Jazz Record Mart’s inventory and of the Delmark Records roster (the label had released both the Estes and the Abrams) spoke to Koester’s capacious but not indiscriminate taste.

Though the JRM’s turntable was presumably there to allow potential buyers to sample sounds before laying down as much as $6 for a new stereo release, Koester frequently disregarded his patrons’ requests to play what he was interested in. He loved the guitar-wielding elders of the Delta blues who’d interested him growing up in Wichita, Kansas, when they provided relief from the white country crooners dominating the area’s radio broadcasts, and he was open to the exploratory and sometimes abstract ideas of the newly formed Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, to whom he’d been introduced by onetime JRM manager Chuck Nessa. But he really favored trad jazz, and he often treated JRM shoppers—representing Chicagoans of every stripe—to music that at the time seemed corny to me. Banjoist Clancy Hayes and his band the Salty Dogs were not universally appreciated.

Koester didn’t care. His approach to retail was idiosyncratic, to say the least—the opposite of Marshall Field’s dictum that the customer is always right. And as it went at the Jazz Record Mart, so did it too at the label financed by the store’s sales. He hired people who contributed their own energies to both, but it was Bob’s empire, and he ran it his way.

Considering the vast amount of good his operations have done for Chicago’s blues and jazz scenes since he moved here from Saint Louis in 1958—good that is now continuing past his death—Koester’s point of view clearly had advantages.

It also had disadvantages, and Reader critic Peter Margasak detailed some of them in 2016, when Koester sold the JRM name and inventory to online collectors’ mecca Wolfgang’s Vault. (Having left expensive downtown real estate behind, two months later Koester opened a shop called Bob’s Blues & Jazz Mart on Irving Park at Kimball.) Bob had arcane protocols for stock control, for Scotch-taping bags, for seemingly everything. Cornetist Josh Berman, who worked in various capacities at the JRM from 1992 to 2009, remembers, “It was crazy town—I don’t think Bob would deny it. He could be very funny about that stuff.”

Kent Richmond, the final JRM manager (he’d come from shuttered rival Rose Records), was shocked and frustrated that Bob’s store tracked merchandise with notations on index cards rather than a computer program, and that despite significant mail-order business Koester was disinterested in building a functional JRM website. Bob rarely took out ads, though he made exceptions for the Reader and for Living Blues, which he’d supported from its launch in 1970. His method of promotion consisted primarily of mailing out a printed newsletter and an obsessively annotated catalog. Still, store and label survived, even thrived.

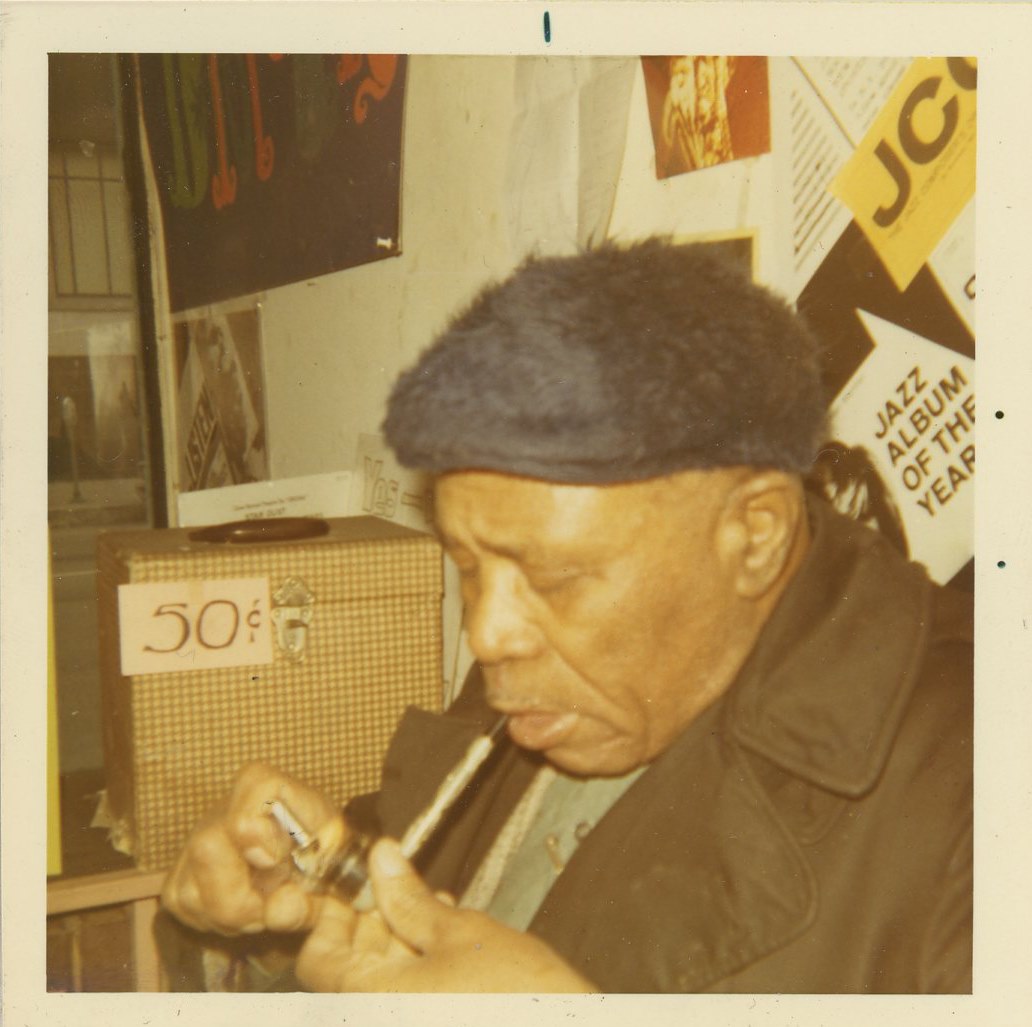

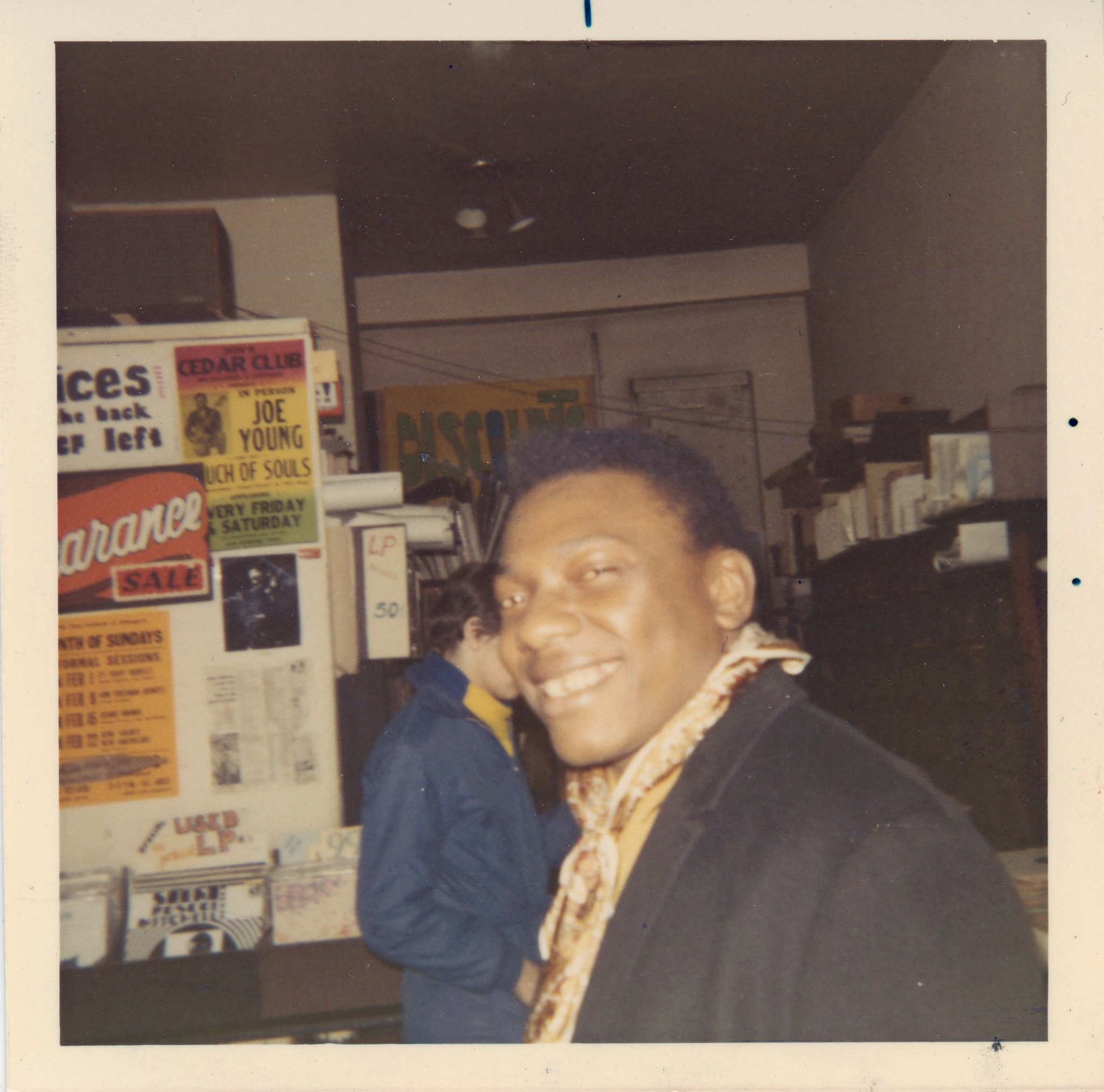

Koester wasn’t always in the shop, and his more consumer-sensitive employees frequently played major roles in creating the ambience that made the JRM an information center and cultural crossroads as well as a moneymaker. Back in the Grand Avenue days, long before the Jazz Record Mart occupied the most upscale of its several locations (at 444 N. Wabash, across from where Trump Tower now stands), gospel-singing blind guitarist Arvella Gray stood outside the front door busking, and Big Joe Williams or Washboard Hank perched just inside on a stool, kibitzing with anybody who came in. Manager Jim DeJong stuck music obituaries and reviews clipped from newspapers to the walls over the record bins, and he also became a trusted source of information on who was performing when and where, including at venues far from the Rush Street entertainment district—editorial assistants would call him for their music listings.

DeJong, who later ran the jazz department at the Clark Street location of Tower Records, sold music differently than Koester, developing insights into what people wanted and might enjoy exploring further. Koester had slight interest in commercial trends and seldom stocked white or Black pop, rock, and R&B, but when it seemed like everyone coming up the subway steps or getting off the bus in front of the Jazz Record Mart needed Curtis Mayfield’s Super Fly, DeJong kept a box of the LPs under the counter, next to a stack of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue to offer the uninitiated. Koester was fine with that, and with DeJong’s to-the-penny accounting, though he’d sometimes mess up his manager’s buying plans by appearing before a late-Friday bank deposit to raid the store’s weekly income so he could cover a Delmark recording session or some personal expense.

“When we made a record, the Record Mart had to stop buying or not pay the rent,” Koester said with a chuckle during a 2018 video interview for the archives of the Jazz Institute of Chicago, which he’d helped found a half century before. That chuckle suggests he knew he was playing fast and loose, but such self-awareness didn’t turn him into a good businessman or boss. Tales persist of Koester dressing down employees in public or firing them capriciously (as he did DeJong), and he could be rude or crude around bystanders. But people devoted to jazz and blues as a lifestyle stuck with Koester (or were stuck with him), drawn into his orbit by his mix of entrepreneurship and blunt, irrepressible energies.

One of those people was Chuck Nessa, hired to manage the Record Mart in 1965 for $50 per week. He wanted to learn how to make jazz records. Koester believed that the independent labels of the 30s and 40s had “missed bebop” due to their moldy-fig attitudes, and in Nessa he saw a way to help Delmark avoid that mistake. He urged his manager to scout for new music and agreed to sign to Delmark three of the Black south-side players who, inspired by the experimental Western classical music introduced to them by Wilson Junior College professor Richard Wang and the iconoclastic jazz coming out of New York City, had just organized themselves as the AACM to focus on original compositions, expanded improvisation, and artistic self-sufficiency.

One year after Koester’s label released Junior Wells‘s debut album, the 1965 Buddy Guy collaboration Hoodoo Man Blues—which spurred Chicago’s second wave of electric blues and is still the imprint’s best seller—Delmark issued Roscoe Mitchell‘s Sound, followed by Joseph Jarman‘s Song For and Abrams’s Levels and Degrees of Light. The production credits read “Robert G. Koester,” but Nessa clarifies: “Though invited, Bob never attended my recording sessions. He said he didn’t really understand the music but felt it was important, that he ‘didn’t speak the language’ and that he might be a distraction.”

Those albums were widely critically acclaimed and have since been recognized as historically important, but they didn’t sell well, and Nessa quit a year into his JRM job after becoming the butt of a Koester tantrum. He continued producing records, and Roscoe Mitchell and Lester Bowie wanted to arrange a studio session together. But when Nessa came to the store to broach the idea to Koester, he was thrown out. By the time the recording was completed in summer 1967, Nessa still intended it for Delmark, but after suffering another of Bob’s rants he decided to do it himself. With the release of Numbers 1&2, top-billed by Lester Bowie and featuring a lineup that would develop into the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Nessa Records was born.

Blues label Alligator Records has a comparable origin story: erstwhile Koester acolyte Bruce Iglauer founded it in order to record Hound Dog Taylor, after Bob repeatedly turned the project down. The Jazz Record Mart sold Alligator’s releases, of course, as it sold Nessa’s—and whatever else it could procure, often on extended credit. Koester might be temperamental or erratic, but he knew his store needed product the same way his label needed new releases. He bought cutouts to sell at a discount, used collections of vinyl or 78s, and eventually the assets of long-gone imprints such as United, Pearl, Aristocrat, and Sackville, which had catalogs of artists only a deep diver like Koester would recognize as valuable.

Delmark and the Record Mart always seemed to run on a frayed shoestring. Bruce Kaplan of Flying Fish Records used to say he’d studied Koester’s business plan carefully, so he could do the opposite. But Delmark has outlasted Flying Fish, which after Kaplan’s death in 1992 was acquired by Rounder Records (and Rounder in turn was swallowed by Concord in 2010). Once-proud Chicago jazz labels Argo, Bee Hive, Black Patti, Bluebird, Cadet, Ebony, El Saturn, and Mercury are gone. Premonition seems to be on hiatus; Okka Disk and 482 Music have left town.

Southport, Aerophonic, Blujazz, Corbett vs. Dempsey, and International Anthem arguably embrace the Delmark model of low production costs and heavy reliance on self-sufficient ensembles led by locals. Respectfully and amicably bought in 2018 by musicians Julia A. Miller and Elbio Barilari, Delmark continues to operate from offices on Rockwell, following the open-minded, tradition-grounded aesthetic Koester established—though it has embraced technology and platform diversity (including licensing deals with streaming services) as a means to sustain its recording endeavors.

Chicago blues labels Blind Pig, Red Beans, Earwig, and the Sirens all formed well aware of Koester’s successes with west-side bluesmen Magic Sam, Luther Allison, Jimmy Dawkins, Jimmy Johnson, Otis Rush, Lonnie Brooks, and J.B. Hutto. They recognized his commitment to harmonica player Carey Bell and his guitar-slinging son, Lurrie, among other up-and-comers Delmark recorded more than once. Fans everywhere acknowledge Koester’s significant documentation of postwar blues and boogie pianists, whose deep Chicago roots had been overlooked by Chess and Vee-Jay, Delmark’s immediate local predecessors.

Indeed, Delmark’s very first LP release was the 1961 album The Dirty Dozens by pianist Speckled Red, recorded in Saint Louis by Erwin Helfer, who’s since become Chicago’s dean of blues, boogie, and roots piano. (He’s also a former Koester friend, and has nothing good to say today about a man he claims denigrated his talent, strung him along about recording, and once shook his hand while Koester’s own hand dripped with barbecue sauce—which Helfer promptly smeared on Koester’s shirt.) Albums of piano blues from Roosevelt Sykes, Sunnyland Slim, Otis Spann (with Junior Wells), Little Brother Montgomery (on a late-career recording by classic 1920s blues singer Edith Wilson), and others followed.

Bob once confided to me that he and his bride had spent their honeymoon night parsing Red’s famously salacious lyrics. No doubt he lied, though he had in fact met the future Susan Koester because she was a customer at the Jazz Record Mart—one who took Bob up on his offer, freely made to many, to tour south-side blues clubs with him at a time when few white people did so. As Bob liked to put it: “I always say my wife fell in love with Junior Wells and settled for me.” It seems most likely that this woman, who lived with him for 54 years, with whom he had two children, and who is believed throughout her circle of acquaintances to possess a saintly calm, patience, and sagacity, fell for his directness, spontaneity, and enthusiasm for all sorts of musical languages, even if he wasn’t fluent in them. He always found ways to express himself.

“We went to some parties of the AACM musicians,” she remembers, “and I got the feeling the guys like Joseph Jarman and Anthony Braxton really liked Bob. They saw him as a complete nonracist. Bob was just Bob, and expected everybody to be that way.”

As part of our 50th anniversary celebration, the Reader is giving out 50 incredible prizes for 50 days. We’ve partnered with some of Chicago’s most popular establishments for prize packages that include concert tickets, theatre tickets, gift certificates to popular restaurants and retailers, and more. The best part is, every Reader Revolution member will be automatically entered to win, no matter what giving level you’re at.BECOME A MEMBER

The thing is: Bob Koester really loved hearing blues and jazz, and he had strong opinions about players famous and obscure, most of whom he’d seen onstage. He loved going out to hear music regardless of where the clubs were or who they catered to, though he could be sarcastic about “whitey” fashionably “discovering” Black music. He complained in the Internet age about the Napster generation’s assertion that “Music should be free!” He was always expected at jazz events—he showed up in Hyde Park for the AACM’s 50th-anniversary extravaganza in 2015, when he was already well into his 80s—and of course for many years he had a Jazz Record Mart tent at the Chicago Jazz Festival.

Bob Koester became a model, positive or otherwise, and provided opportunities for musicians as well as for nascent producers, critics, and visual artists. Perhaps in spite of himself, he created a space where communities, cadres, and coteries coalesced.

During Josh Berman’s tenure, other clerks included reedist Keefe Jackson, vibraphonist Jason Adasiewicz, drummer Frank Rosaly, guitarist Joel Patterson, drummer Nathan Greer, and guitarist Steve Dawson; among Koester’s employees in earlier eras were Jazz Showcase founder Joe Segal, harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite, keyboardist and producer Pete Wingfield, guitarist Mike Bloomfield, and pianist Miguel de la Cerna, whose parents had run a newstand at Grand and State. Besides Nessa and Iglauer, future producers Pete Crawford, Steve Dolins, Dick Sherman, and Steve Wagner worked with, for, or around Delmark, where many of them learned their way around a recording studio. John Litweiler, J.B. Figi, and Terry Martin wrote important liner notes for Delmark, introducing the AACM to the world. George Hansen drew hilarious cartoon album art, and D. Shigley and Marc PoKempner took cover photos for the label.

Cliques formed at the Jazz Record Mart, and love affairs no doubt started there. But it was mostly a place to go to listen, browse, and have a chat about music, art, Chicago, life, the weather, the mayor, or anything at all with virtually anybody. Multiple-horn-playing phenomenon Rahsaan Roland Kirk would spend a day there, schmoozing easily with shoppers he couldn’t see. Singer Betty Carter came in to personally sell her Bet-Car albums, as did Alton Abraham, manager for Sun Ra, with a new batch of platters from the boss. Delmark artists showed up for payments. DJs and presenters bumped into each other.

“I met so many people I would never have met,” Berman says. “The Mart was downtown-ish, between the north side and south side, so there was a lot of intermingling. White folks, Black folks, young guys, old guys, women, students, tourists, postmen, cops, annoying people, fantastic people . . . How would you get that today? I have no idea. We were lucky.”

Such luck is still possible. When Koester had a stroke in early December 2020 that landed him in the hospital for a month (and from which he never really recovered), his son, Bob Jr., took over Bob’s Blues & Jazz Mart. He plans to keep it open. “I didn’t realize he was that interested,” says Susan Koester, Bob Jr.’s mother. “But he says he is. I guess retail’s in our blood.”

I had first met Bob Koester Sr. in 1966, on my 16th birthday, lured by a small ad promising post-Christmas discounts across Jazz Record Mart’s whole inventory. I’d hung around there throughout my teens, sweeping the floor, going out for coffee or pizza when sent, filing, or selling—and sopping up as much about music, musicians, and music lovers as I could. I worked there formally for a year or so after college in the early 70s, and throughout the decades I’d return to say hi, buy a couple records, check out the scene. Bob would always tell me I’d gotten fat—definitely so, compared to when he first knew me.

In the past five years, as Koester coped with his increasingly undependable memory, he didn’t always recognize me. I’d identify myself, and then he’d tell me again that I’d gotten fat. But the last time I stopped in at Bob’s Blues & Jazz Mart, before the pandemic, I pushed through the door and he looked up and said, “Welcome home.” He might have said the same to anyone attracted to or immersed in Chicago’s jazz and blues worlds. It was perfectly true.

Bob Koester, Revered Figure in Jazz and Blues, Dies at 88

Mr. Koester’s Delmark Records and his Chicago record store were vital in preserving and promoting music the big labels tended to overlook.

By Neil GenzlingerMay 15, 2021

Bob Koester, who founded the influential Chicago blues and jazz label Delmark Records and was also the proprietor of an equally influential record store where players and fans mingled as they sought out new and vintage sounds, died on Wednesday at a care center in Evanston, Ill., near his home in Chicago. He was 88.

His wife, Sue Koester, said the cause was complications of a stroke.

Mr. Koester was a pivotal figure in Chicago and beyond, releasing early efforts by Sun Ra, Anthony Braxton, Jimmy Dawkins, Magic Sam and numerous other jazz and blues musicians. He captured the sound of Chicago’s vibrant blues scene of the 1960s on records like “Hoodoo Man Blues,” a much admired album by the singer and harmonica player Junior Wells, featuring the guitarist Buddy Guy, that was recorded in 1965.

“Bob told us, ‘Play me a record just like you played last night in the club,’” Mr. Guy recalled in a 2009 interview with The New York Times, and somehow he caught the electric feel of a live performance. In 2008 the record was named to the Grammy Hall of Fame.

About the same time, Delmark was recording early examples of the avant-garde jazz being promulgated by the pianist Muhal Richard Abrams and other members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, an organization formed in Chicago in 1965. The company’s recordings were not, generally, the kind that generated a lot of sales.

“If he felt something was significant, he wasn’t going to think about whether it would sell,” Ms. Koester said by phone. “He wanted people to hear it and experience the significance.”

As Howard Mandel, the jazz critic and author, put it in a phone interview: “He followed his own star. He was not at all interested in trends.”

For decades Mr. Koester’s record store, the Jazz Record Mart, provided enough financial support to allow Delmark to make records that didn’t sell a lot of copies. The store was more than an outlet for Delmark’s artists; it was packed with all sorts of records, many of them from collections Mr. Koester bought or traded for.

Editors’ Picks

You Got Lost and Had to Be Rescued. Should You Pay?It’s Time to Stop Paying for a VPN5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Maria CallasContinue reading the main story

“The place was just an amazing crossroads of people,” said Mr. Mandel, who worked there for a time in the early 1970s. Music lovers would come looking for obscure records; tourists would come because of the store’s reputation; musicians would come to swap stories and ideas.

“Shakey Walter Horton and Ransom Knowling would hang out there, and Sunnyland Slim and Homesick James were always dropping by,” the harmonica player and bandleader Charlie Musselwhite, who was a clerk at the store in the mid-1960s, told The Times in 2009, rattling off the names of some fellow blues musicians. “You never knew what fascinating characters would wander in, so I always felt like I was in the eye of the storm there.”

Mr. Mandel said part of the fun was tapping into Mr. Koester’s deep reservoir of arcane musical knowledge.

“You’d get into a conversation with him,” he said, “and in 10 minutes he was talking about some obscure wormhole of a serial number on a pressing.”

Ms. Koester said the store held a special place in her husband’s heart — so much so that when he finally closed it in 2016, citing rising rent, he opened another, Bob’s Blues and Jazz Mart, almost immediately.

“He loved going into the studio in the days when he was recording Junior Wells and Jimmy Dawkins,” she said, “but retail was in his blood.”

He especially loved talking to customers.

“Often they came into the store looking for one thing,” she said, “and he pointed them in another direction.”

Robert Gregg Koester was born on Oct. 30, 1932, in Wichita, Kan. His father, Edward, was a petroleum geologist, and his mother, Mary (Frank) Koester, was a homemaker.

He grew up in Wichita. A 78 r.p.m. record by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in his grandfather’s collection intrigued him when he was young, he said in an oral history recorded in 2017 by the National Association of Music Merchants. But, he told Richard Marcus in a 2008 interview for blogcritics.com, further musical exploration wasn’t easy.

“I never liked country music, and growing up in Wichita, Kansas, there wasn’t much else,” he said. “There was a mystery to the names of those old blues guys — Speckled Red, Pinetop Perkins — that made it sound really appealing. Probably something to do with a repressed Catholic upbringing.”

College at Saint Louis University, where he enrolled to study cinematography, broadened his musical opportunities.

“My parents didn’t want me going to school in one of the big cities like New York or Chicago because they didn’t want me to be distracted from my studies by music,” he said. “Unfortunately for them, there were Black jazz clubs all around the university.”

He also joined the St. Louis Jazz Club, a jazz appreciation group. And he started accumulating and trading records, especially traditional jazz 78s, out of his dorm room. The rapidly growing record business crowded out his studies.

“I went to three years at Saint Louie U,” he said in the oral history. “They told me not to come back for a fourth year.”

His dorm-room business turned into a store, where he sold both new and used records.

“I’d make regular runs, hitting all the secondhand stores, Father Dempsey’s Charities, places like that, buying used records,” he told The St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1993 for an article marking the 40th anniversary of the founding of his record label. “And I’d order records through the mail. Then I’d sell records at the Jazz Club meetings. That was the beginning of my retail business.”

He had started recording musicians as well. He originally called his label Delmar, after a St. Louis boulevard, but once he relocated to Chicago in the late 1950s he added the K.

He acquired a Chicago record shop from a trumpeter named Seymour Schwartz in 1959 and soon turned it into the Jazz Record Mart. His label not only recorded the players of the day but also reissued older recordings.

“He loved obscure record labels from the ‘30s and ‘40s, and he acquired several of them,” Mr. Mandel said. “He reissued a lot of stuff from fairly obscure artists who had recorded independently. He salvaged their best work.”

Mr. Koester was white; most of the artists he dealt with were Black.

“He was totally into Black music,” Mr. Mandel said. “Not only Black music, but he definitely gave Black music its due in a way that other labels were not.”

That made Mr. Koester stand out in Chicago when he went out on the town sampling talent.

“When a white guy showed up in a Black bar, it was assumed he was either a cop, a bill collector or looking for sex,” Mr. Koester told blogcritic.com. “When they found out you were there to listen to the music and for no other reason, you were a friend. The worst times I had were from white cops who would try and throw me out of the bars. They probably thought I was there dealing drugs or something.”

It was the atmosphere of those nightclubs that he tried to capture in his recording studio.

“I don’t believe in production,” he said. “I’m not about to bring in a bunch of stuff that you can’t hear a guy doing when he’s up onstage.”

In addition to his wife, whom he met when she worked across the street from his store and whom he married in 1967, Mr. Koester is survived by a son, Robert Jr.; a daughter, Kate Koester; and two grandchildren.

Ms. Koester said their son will continue to operate Bob’s Blues and Jazz Mart. Mr. Koester sold Delmark in 2018.

Mr. Koester’s record company played an important role in documenting two musical genres, but his wife said that beyond playing a little piano, he was not musically trained himself.

“He would say his music was listening,” she said.

One thought on “REMEMBRING BOB KOESTER – Wonderful 18 (!) page tribute in LIVING BLUES magazine to Delmark and Jazz Record Mart’s founder, the one and only, Bob Koester!”